O Fès! In you are gathered all the beauties of the world. How many are the blessings and riches that you bestow on your inhabitants. The challenge will tax man's capacities and imagination to the full. —Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow

Recently, Hujaina wrote: "What the west likes about the orient is not what the orient likes about the west. we like what is modern in your countries. You like the archive in our countries". And of course she is right. But it made me stop and think about why Westerners would bother to spend so much time and money restoring a dar or riad in the old medina.

Of course there is no single simple answer, but rather a range of answers. Let's start with the historical perspective:

As Geoff Porter once wrote:

Upon Independence from the French in 1956, Moroccans rejected imposed traditionalism. The 1960s saw the destruction of large swathes of the medinas, the installation of electric lines, the ripping up of paving stones in medina alleys for new sewers, and the demolition of centuries-old homes to make way for new roads wide enough for cars. The 1960s were a decade of frenetic catching-up. In the rush to put Morocco on par with the other industrial economies of the 20th century and in reaction to the paternalistic ghettoization that the medinas had undergone during the colonial period, Morocco's architectural heritage was relegated to a secondary status.

But by the late 1970s and then especially in the 1980s, upper-class Moroccans began to realize that this architectural legacy of monuments and cities had value. It had value as reminders of Morocco's illustrious past, as markers of what Morocco had achieved, and hopefully, what Morocco could achieve again. The buildings, the mosques, the homes, the palaces, the entire cities were hallmarks of a great civilization. They were evidence of this admirable past and they were indications that Morocco could again achieve cultural distinction on the global stage.

Porter is right, but he misses one critical point. Architectural legacy is also important for tourism and it is tourism that can be an ongoing force for increasing the wealth of the society.

Porter is right, but he misses one critical point. Architectural legacy is also important for tourism and it is tourism that can be an ongoing force for increasing the wealth of the society.The massive public projects are being run by Abdellatif El Hajjami, director general of the restoration project, known officially as the Agence pour la Dédensification et la Réhabilitation de la Médina de Fès. As the New York journalist Josh White wrote back in 1993... An architect by profession and a native of Fès, El Hajjami has served in his post since it was created almost 10 years ago.

Using two main offices, one in a restored merchant's home near the Palais Jamaï in Fès El Bali - Old Fez - and the other in a discreet villa in the French-built Ville Nouvelle, El Hajjami frequently works 18-hour days. "To know something like this, you must live with it," he says. His duties go far beyond those of an architect: He directs a staff of 160 workers and artisans, including an engineer, three architects, an archeologist, a geologist, a lawyer and various computer and documentation specialists.

The restoration project has already identified 11 madrasahs, 320 mosques, 270 funduqs and over 200 hammams (public baths), houses or public ovens worthy of preservation. Some structures are famous: The Karaouine Mosque, the Bou Anania madrasah, the Horlogerie (a clepsydra, or water clock), the Nejjarine Fountain and the Funduq Nejjarine are but a few. Others are only known to locals, who feel they nonetheless represent key aspects of the city's cultural heritage.

The question arises as to how individuals restoring riads or dars assists this process. Simply put, apart from the money they contribute to the economy of the medina, they are also employing traditional artisans whose skills must be preserved in order that the grand buildings of public significance can also be restored in the correct way. However, money itself is not the answer, as we saw recently with the attempts to restore public fountains in Fès. Much of the work was second class, the zellij work was not up to an acceptable standard.

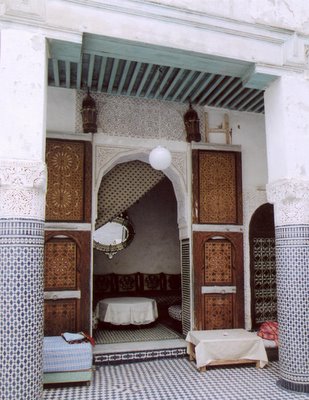

The individual Westerners have not only the money to restore buildings and employ craftsmen, but also the time to devote to research the best ways of restoring. The buzz words are "conservation restoration"... in otherwords, not simply pulling "old stuff' down and building new, but keep what is worthwhile and restore around it. A fine example of this was some work being done by David, a friend of mine who was working on restoring an old medersa and found he needed hand-made nails. It took him weeks to find a craftsman (in Meknes) who could produce the nails, but David's sense of "conservation restoration" was such that he insisted that the nails be made in a slightly different size from the originals so that an expert could tell what was genuinely old and what was restoration. Such is the task at hand for those wishing to restore the grand riads and exquisite dars of Fès.

Of course man of the local inhabitants want to get out into the "modern world" and even if the did not they could not afford the cost of restoration. The Westerners can and should. And, in my experience, the local people appreciate that someone cares enough to restore the old houses to their former glory.

Link: : Everything you need to know about Fès

Tags: Morocco, Fès, travel, House in Fez

1 comment:

The water clock is opposite Medersa Bou Inania, but connected to this school, is a medieval water clock, consisting of 13 windows and platforms - seven of which still retain their brass bowls. High over them on a carved lintel of cedar is a decaying row of 13 windows. Forgotten for centuries, the clock is being renovated and hopefully, in the future, experts will be able to have it working again.

And as for parking cars. I will not have a car in Fes, but if I did there is a car park at R'Cif.

Post a Comment