Lynnsay Maynard, former public radio producer/host at MPBN, now manuscript reader at Electric Literature, Brooklyn, New York, USA, reflects on the work of Paul Bowles in recording and preserving Morocco's traditional music and the role of the American Legation in continuing his work

|

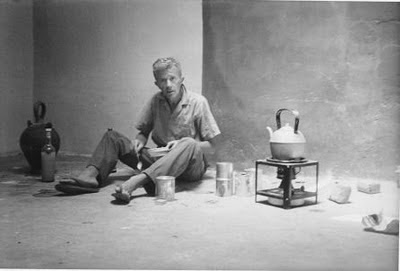

| Paul Bowles ~ photo by Jearld F Moldenhauer courtesy Dar Balmira Gallery, Gzira, Fes Medina. |

In early March of 1959, the first performances of Tennessee Williams’ play “Sweet Bird of Youth” opened at Martin Beck Theatre in New York City starring Paul Newman and Geraldine Page. Directed by Greek-American Broadway and Hollywood legend Elia Kazan, most famous for conceptualizing ‘method acting’, the production of the Hollywood-lustful gigolo Chance Wayne would go on to garner four Tony Award nominations and enjoy over 350 performances in its initial run. Hidden amongst the dazzling list of cast and crew was the production’s composer: Paul Bowles, an American composer and author known preeminently for his 1949 novel “The Sheltering Sky” and his notoriously colorful expatriate lifestyle in his adopted home base of Tangier, Morocco.

Bowles was busy in 1959. A collection of his short stories, “The Hours after Noon”, was published. From Tangier, he was caring for his wife, writer Jane Bowles, who had suffered a debilitating stroke two years prior. A lifelong friend and collaborator of Williams, “Sweet Bird of Youth” marked the third production to which Bowles penned the music. And in the spring, Bowles was awarded a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation totaling $6,800 to fund an expansive project in conjunction with the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (LOC): travel across Morocco and record as much folk, tribal and modern music as possible.

After a weeks’ training on Ampex reel-to-reel recording equipment at the LOC in Washington D.C., Bowles returned to Tangier. In early August, Bowles set out in a Volkswagen Beetle stocked with equipment, bedding and pots and pans accompanied by Christopher Wanklyn, a subdued American associate of Bowles’, and Mohammed Larbi Jilali, a kif-dependent native Moroccan who knew the local officials and the terrain.

My stint, in attempting to record the music of Morocco, was to capture in the space of the six months which the Rockefeller Foundation allotted me for the project, examples of every major musical genre to be found within the boundaries of the country... By [December 1959]... I already had more than two hundred and fifty selections... as diversified a body of music as one could find in any land west of India. - Paul Bowles Their Heads Are Green ("The Rif, To Music")During four, five-week trips separated by days of respite in Tangier, the trio zipped across Morocco visiting 23 cities and towns along the Rif and Atlas Mountains, northern Sahara and southeastern and northern corners operating from a map of Bowles’ design. In his essay, “The Rif, To Music”, Bowles details portions of the trip including terse negotiations over performance costs, audible gunfire from Oujda, a town 5km west of Algeria which was in the throes of its revolution against French forces and the unbridled joy of a hot shower after days of traversing unpaved back roads.

The trip yielded 72 reel-to-reel tapes, a total of 250 selections of Moroccan music. Bowles returned the recordings to the American Folklife Center at the LOC. The recordings languished in Washington D.C. until 1972 when Bowles handpicked 20 selections for a two-LP set published by the LOC.

As a composer, Bowles was personally interested in the music but his true investment in the, at times, exhausting, four-month venture was in the preservation of an oral culture that encompassed the people and tradition of Morocco. In “The Rif”, Bowles writes, “The most important single element in Morocco’s folk culture is its music….the entire history and mythology of the people is clothed in song. Instrumentalists and singers have come into being in lieu of chroniclers and poets, and even during the most recent chapter in the country’s evolution – the war for independence and the setting up of the present pre-democratic regime – each phase of the struggle has been celebrated in countless songs.”

A protectorate of France and Spain since the mid-19th century, Morocco gained independence in 1956 when the previously exiled Sultan Mohammed V became king. The monarchy wanted to be seen as modern and resisted the presence of a notable American recording traditional Moroccan music, an experience that Bowles recounts through numerous examples in “The Rif”.

|

| American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies |

Gerald Loftus, (pictured left) director of the Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies (TALIM or, colloquially, the American Legation Museum), credits Bowles for preserving Morocco’s musical heritage at a pivotal time in the country’s history.

“If you look at some of Paul Bowles’ writings, he was worried that some of this music would disappear. He was aware of the fact that the Moroccan government at the time was not terribly enthused about a foreigner recording their music, what they saw as primitive music. They were Western-educated: they wanted to be seen as modern and this was seen as primitive,’ said Loftus.

Nestled on a residential street of Tangier’s medina, or ‘old city’, the American Legation building was gifted to the United States in 1821 by Sultan Moulay Suliman and served as a US consulate and later legation, as well as a heavily trafficked post for World War II intelligence agents and a Peace Corps training facility. Today, its courtyards and narrow hallways serve as an elaborate museum demonstrating American-Moroccan relations and Moroccan heritage, including an entire wing devoted to Bowles.

|

| Paul Bowles, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso and Ian Sommervill in Burroughs’s Villa Mouniera garden, Tangier - July 1961 |

A cluster of rectangular rooms with jade green tiles positioned off a lush terrace, the Bowles wing is a venerable monument to the artist’s life and work. A typewriter sits perched on five-tiered stack of faded, tired luggage below a photo of Bowles at the keyboard, with a quote from the author denying that he ever used a typewriter. A framed snapshot of Bowles, barefoot before a fire with a notebook and pen in hand, is signed ‘Allen Ginsberg’. A scrapbook from one the American School of Tangier’s high school play, “The Garden”, to which Bowles contributed incidental music, lies adjacent to a scattered array of typewritten postcards. Loftus taps on the glass case and gestures towards the pile.

“Some of them I turned over; they might be semi-pornographic on the other side. Some of these are business correspondence. It’s like sending an e-mail today from your literary agent to Paul Bowles,” said Loftus, peering over a postcard languishing in the middle of the pile.

Loftus, a former US Foreign Service Officer, took the helm as director of the American Legation in 2010, a year that also happened to mark the centenary of Bowles’ birth. Working with a minimal amount of artifacts compiled 15 years prior by Gloria Kirby, a lifelong Tangier resident and friend of Bowles, Loftus reached out to connections at cultural institutions and notable Tangier expats to expand the existing collection, with a new focus in mind: Paul Bowles the composer, including an entire nook devoted to the 1959 project.

In 2010 when Loftus became director, he had a series of consultations in Washington D.C. before jetting off to Tangier. A meeting at the LOC precipitated a conversation with Michael Taft, former head of the LOC archive, and Judith Gray, a reference specialist at the American Folklife Center. Gray mentioned the Bowles tape in LOC archives and stressed the importance of digitizing the material, a growing trend the American Folklife Center and LOC.

“All of us would have been speaking about digital preservation as the major task needing to be done before any other types of projects, including dissemination of recordings back into Morocco, could be undertaken,” said Gray.

The same year Loftus became director of TALIM, he secured funding from the US Embassy Public Affairs Section in cooperation with the LOC to digitize and repatriate the 72 reel-to-reel tapes to Morocco and its people. Sound Safe Archive in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, remastered each reel before the entire collection was burned to four sets of CDs, which were sent to Morocco with the intention of distributing them to the Moroccan Ministry of Culture, the Wilaya (an administrative district) of Tangier and His Majesty King Mohammed VI, with the fourth and final set remaining at the American Legation as an educational and research resource.

|

| Paul Bowles' typewriter - "I never used a typewriter!" |

In the Bowles wing of the American Legation, a small sign details the digitization process and credits the Moroccan Ministry of Culture as a partner in the undertaking. In 2010, Loftus signed detailed agreement with the Wali of Tangier and the then Minister of Culture, Bensalem Himmich, delineating the transfer of the remastered CDs and the small portion of the digitization fees the Moroccan government agreed to pay. Despite the funding originating from the US Embassy, Loftus said he wanted the Moroccan people to reap the benefits.

Following the agreement and initial fervor for the project, Moroccan officials have yet to claim the material or pay their portion of the agreed upon fee. Loftus’ tenure as director of TALIM will end June 2014; as he prepares for his departure, Loftus hopes to wrap up the four-year-old agreement so Moroccans can enjoy their musical heritage, many of whom are completely unaware of Bowles’ country-wide trek.

In 2012, Loftus appeared on a two-hour Radio Tangier panel discussion about Paul Bowles wherein he described TALIM’s project and brought select samples of Bowles’ recordings to play on-air. The panel, save Loftus, was comprised of native Moroccans.

“They were all familiar with Paul Bowles and his work on music but they had never heard these selections before. They were speechless. It was speechless radio because they were in awe of what he had recorded in 1959,” said Loftus.

While Loftus is also working to host the remastered selections online for global dissemination, his utmost desire in repatriating the recordings are aligned with Bowles’ mission in 1959: to share the preserved music of Morocco with its people.

“It is Morocco’s music recorded by an American and now, it’s back in Morocco,” said Loftus.

Read more from TALIM HERE

SHARE THIS!

No comments:

Post a Comment